Saturday (I think today’s Saturday; it makes little difference to shipboard routine) dawned bright and sunny, quite different from yesterday, with light and variable wind, flat seas. That made for easy conditions in which to retrieve mooring A; the team snatched it from the water in no time flat. After doing so, we moved inshore, where they planted a “bottom lander” to measure the local tidal range. We’re back within several miles of Africa, a mysterious, seemingly uninhabited coastline edged by high sand dunes and low scrub. I wonder what lies over the hill. But now we’re steaming away from the beach to re-deploy an effectively weighted mooring A.

Our bird, a Cape turtledove, having been blown offshore, took refuge aboard Knorr over a week ago. Land birds often find their way aboard research-vessel life rafts, but they usually stand forlorn and confused, feathers puffed, then die within a few days despite our attempts to feed and water them. No one has known a land bird to survive as long as this one, long enough to gain a name, Rusty. He (she?) is eating bread, crackers, sunflower seeds, and hopping around deck like an able bodied seaman. We were hoping that when his native habitat hove into sight, he’d notice and fly home, but he didn’t. Has he taken to this shipboard life? Maybe he’ll make it back to Cape Town with us, tell fantastic sea stories to credulous urban avians.

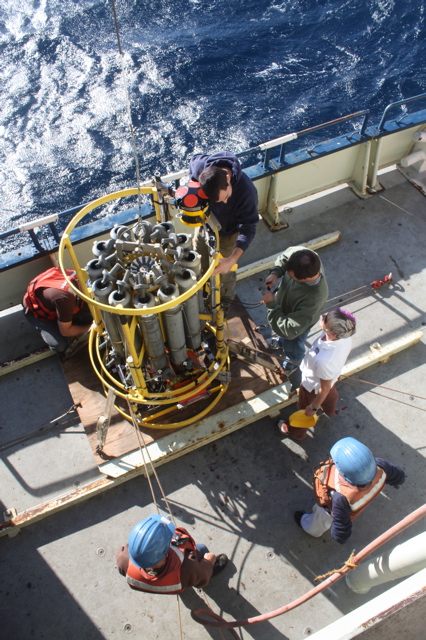

After we splash mooring A, the heavy lifting will be complete, and everything Lisa means to leave behind will be in the water and, we hope, working. Only “hydrography” remains. That’s when the so-called CTD and its team of operators will swing into action, working two 12-hour shifts each day. (Truth to tell, they’re not delighted at the prospect.) The CTD is a package of multiple instruments, usually referred to as “the package.” If oceanography were carpentry, the CTD would comprise the most basic of tools, hammers and saws. CTDs are used on every physical oceanographic cruise, no matter its primary objective. At its most basic, the CTD provides a full-depth temperature-and-salinity profile of the water columns through which it’s repeatedly lowered and raised. Temperature and salinity comprise the main components of water identity, and that’s why CTDs are used on every cruise.

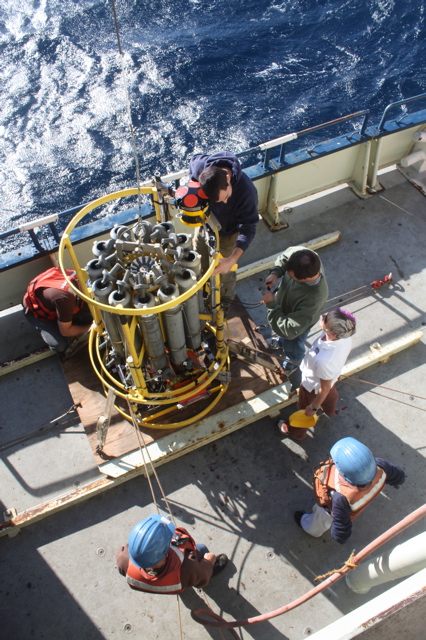

The package weighs about a ton. You have to stand up on the frame to see the top. At first glimpse, you notice only the twelve gray plastic water-sampling bottles, like skinny scuba tanks, mounted upright in a ring around the frame. You have to look beneath the bottles to see the sensors, batteries, pumps, and the rest of its innards.

“C” stands for conductivity. Skipping over the intricacies, suffice it to say that if you can measure how readily a small pulse of electricity passes through the water, you can with a computer and the application of some algorithms determine seawater salinity to a high degree of accuracy, because the pulse passes differently through salty and less-salty water. “T” stands for temperature, pretty self-explanatory. And “D” stands for depth, essential since if the objective is to measure the entire water column, you need to know where in it the salinity/temperature measurements are taken.

The ship is brought to a stop at each of Lisa’s predetermined positions, about 40 on this trip. The package is hauled out of its home in the hanger onto the starboard side deck. A crane operator lifts it off the deck then lowers it on a wire to within about 20 meters of the bottom, which of course requires that the operators know the depth before each cast. (On every cruise you hear stories about wildly inattentive operators who let the package slam into the bottom and the wire unspool on top of it, but of course there are no inattentive operators on this boat.)

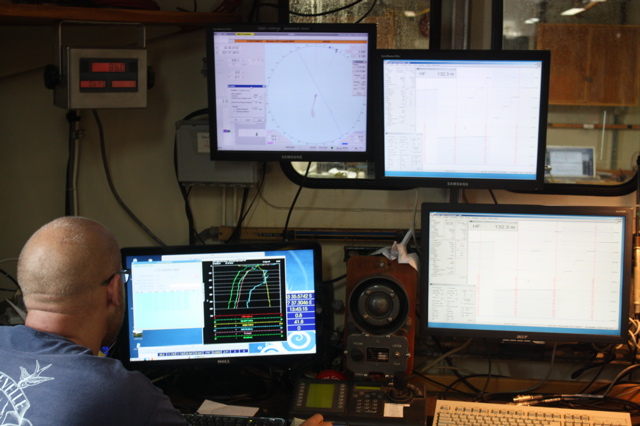

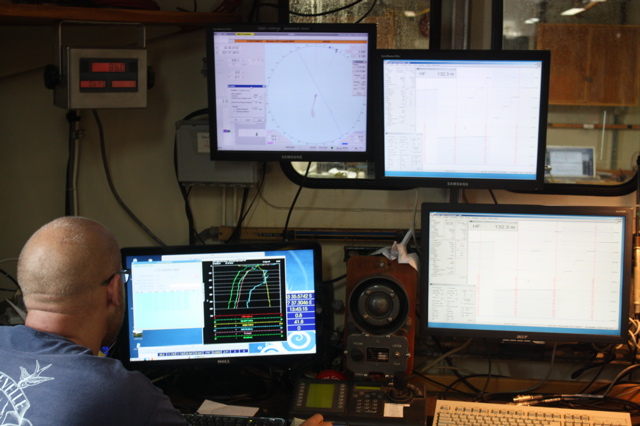

The package is gradually hauled back up, stopping at predetermined depths; at each, the operator receives temperature/salinity data projected automatically up the wire to the CTD console, a screen that visually records temperature/salinity (T-S) data linked to a computer. The operator notes the data on paper, then “fires” one of twelve bottles with the press of a computer key, and the spring-loaded bottle caps snap shut—capturing a water sample. The bottles must remain open as the package goes down; closed bottles would be crushed flat by the enormous water pressure at depth. (One CTD amusement is to write greetings, quips, and things on Styrofoam coffee cups and send them down with the package. They come back thimble-sized. I haven’t seen any cups yet. I guess this crew is too sophisticated for such juvenilia.)

In addition to the basic sensors, Lisa has attached two ADCPs, one looking up, the other down, for a series of full-profiles of Agulhas Current velocity. That should cover all the bases.

I went on my first cruise as volunteer CTD operator. A complete rookie, I didn’t know temperature from salinity, and each time I lowered the package to within about 250 meters of the bottom, the not-unreasonably edgy chief scientist would appear over my shoulder trying to look nonchalant as I continued the cast. “The most important thing to remember about the CTD,” he’d say, “is don’t hit the bottom.”

Novelty will break the routine tomorrow. We’re supposed to rendezvous with a Dutch sailing vessel, the Clipper Stad, said to be duplicating the famous voyage of the Beagle on which Charles Darwin circled the world in the 1820s. Lisa knows one of the scientists aboard. Such at-sea “gams,” as they used to be called, are tricky to pull off particularly under sail. I’ll keep you posted.