At this writing shortly after breakfast, the last mooring is going out. It’s a long one, 4,000 meters—that’s 2.48 miles. We’ve been extremely lucky with the weather, four days of light winds and flat seas, only the long, lazy swell to remind us we’re floating on a vast ocean basin. I hear, however, that the weather is going to take a hard turn for the worse. The African met service is forecasting 40 knots to land on us after midnight from the northeast. That’ll sort us out, send people scurrying for the medicine cabinets. Wind always determines quality of life. But we might have encountered that nastiness in the middle of mooring ops, so no complaints are justifiable.

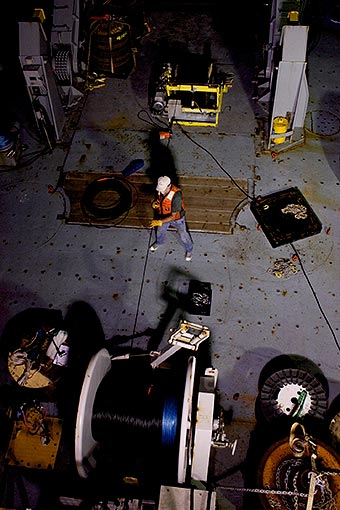

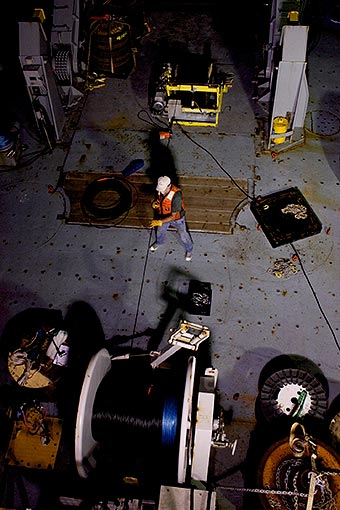

As on previous cruises, I’ve been thinking as I watched the mooring work about that unique, braided combination of heavy industry, electronic technology, sophisticated science, and seamanship required to measure an ocean. All these elements must meld as one, and when they do—they don’t always—success is likely, if not guaranteed. But, as always, that depends at each step and all departments on people.

Last evening I found Benita, a South African ocean technologist, sitting in the mess room with a cup of tea. She’s been working hard on the after deck with Robert, Mark, Cedric, and the others throughout mooring operations.

“You look like a tired lady,” I said.

She was, she said, but happy. “During that first fire drill, I looked around at all the strangers and wondered how we’d all get along. But now we’re like a team that’s worked together for years.”

Robert joined us, and we kidded Benita about how hard it must be for her hanging around with all these bloodyAmericans. But there’s a serious point here, reflected by Benita’s experience, having to do with the special way of life about research vessels. We walk aboard from several different continents with disparate sets of experience, some of us veterans of various oceans, some others of us green hands in grad school. But it doesn’t take long, not usually anyway, for firm friendships to form. This has something to do certainly with the fact that, unlike shoreside endeavors, our workplace and living spaces are contained within 280’ of hull. But it’s more than that. It has to do with the work itself. We’re not taking anything, harming anything, merely trying to understand how the ocean works.

Now, pardon me, I don’t mean to go all sentimental (though there’s something about the ocean and ships...) or self-congratulatory; and while I can’t claim pure objectivity, it seems to me we have a great group. The students are avid, smart, and congenial. And the old pros are more than willing to share their knowledge and experience. It’s a lovely dynamic to observe, and I’m pleased to be a small part of it.

But then inherent in the quickly forming friendships is abrupt separation. In less than two weeks, we’ll put in at Durban and shortly afterwards return to our respective continents. However, at-sea oceanography is a small world and there are only a few research vessels. Courses tend to cross and re-cross.

They just dispatched the last mooring anchor on its 40-minute trip to the bottom. An albatross circled in our wake, wingtips ticking the short waves.