"When you put an instrument in the water," goes the oceanographic axiom, "you no longer own it, the ocean does, and it may or may not give it back." Today it refused to return our tide gauge. It's always a tense moment when from the "deck box" Robert pings the acoustic release set at the bottom of the mooring above the anchor. The release pinged back in acoustic code, "I'm awake and ready for orders." Robert ordered it to relinquish its hold on the instrument, and the release obeyed. Lisa and the enthusiastic students trooped to the bridge to spot the big round float when it popped to the surface. The gauge was only 60 meters down; travel time from the bottom, under three minutes. But it didn't pop to the surface.

Perhaps it had sunk in the silt, perhaps marine growth had fouled the connection to the release.

Perhaps,well, perhaps the ocean had grown fond of it. Who knows? But you can't just leave it down there, a $5,000 instrument with its far more valuable stored data, and sail away.

"So let's go fishing," said the Captain Kent. The brain trust Chief Scientist Lisa, Pete the bosun, Mark the mooring tech, and the Cap assembled by radio to figure out how to drag for the thing.

Because the ocean is typically stingy in returning loaned instruments, there is a well-practiced "fishing" method aboard Knorr: deploy a weighted wire off the stern, maneuver the ship such that the trailing wire forms a horseshoe shape around the submerged instrument, then snag it by dragging the wire over instrument's bottom position so they tried that first. However, unlike typical moorings, the tide gauge was a low-slung thing with no handy protrusion to snag; in order dislodge it, they had to actually hit it. This would be tricky, since the bottom here is rocky.

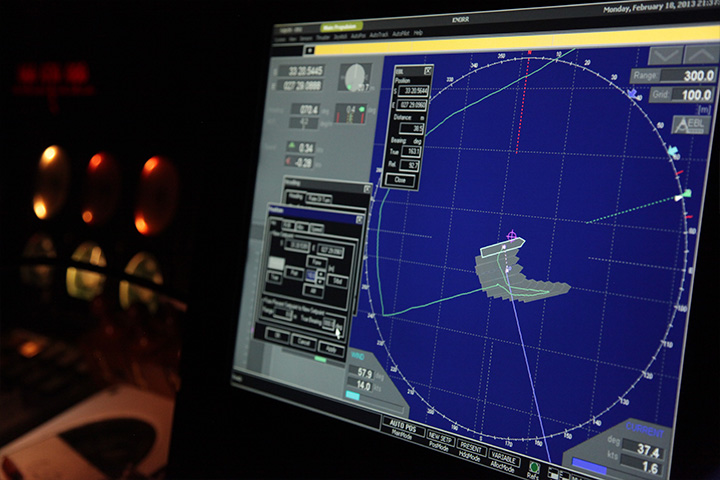

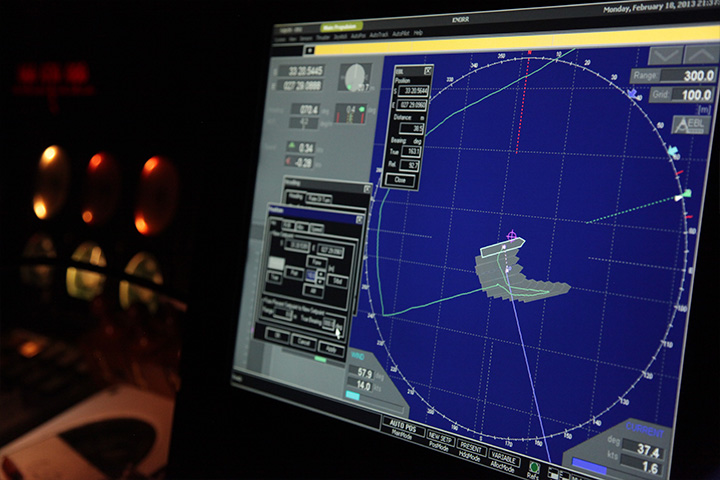

For us gawkers on the bridge, it was like watching a nautical video game, because the "geographical" position of the instrument and the track of the ship were graphically displayed on the big GPS screen. We watched Cap carve his turn around the objective, and then he radioed Pete to slowly haul in the wire.

An instrument on the bridge displays the degree of tension on the wire, and every time we saw the tension jump, our hopes jumped with it. But, no, it didn't turn up the instrument; the trawl wire was probably snagging and bouncing over rocks.

"Deck, bridge"

"Go ahead, Captain," Pete the bosun replied from the transom.

"I'll move closer and let's try again."

"Roger that."

The process, so brief to describe, had begun in the late afternoon, extended through dinnertime, and now it was full dark, only the red glow the instruments to light the bridge. Again, pay out the wire, maneuver the ship to trail the wire over the site.Time passing, our excitement at the outset had faded with the daylight, and now we seldom exclaimed when the wire tension surged. The second trawl turned up nothing.

Cap pondered the problem in silence, and then, head-down determined, vanished from the bridge, appearing moments later on the transom to consult his bosun and Mark the tech. From the bridge we could see them point at the winches and illustrate alternative possibilities with their hands. These guys meant to retrieve this thing from the ocean's clutch if it took all night. Which it might. By the time Cap returned to the bridge, we saw the deck guys flaking out a heavy line and shackling chain to it. "Okay," he said, "I'm going to park the stern right over the [bleep/bleeping] thing."

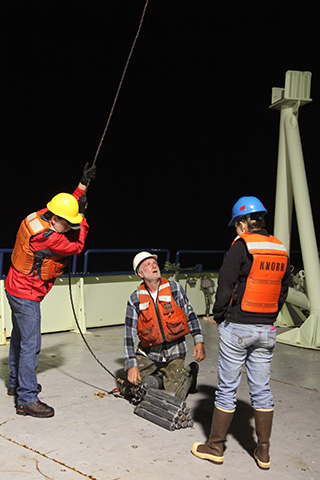

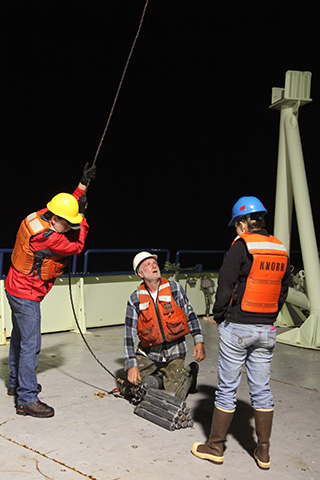

Oh, I see, he meant to make a bight in the heavy line, weight it so it drags along the bottom, drop it right over the thing, then use the ship to drag over the instrument. It was blurry-eyed midnight by the time the rig was ready to go overboard. Derek had relieved Jen as watch officer.

"Okay, Derek, it's on you."

"Got it." He edged Knorr forward. We all looked outboard for the strobe light mounted on the tide gauge. Nope. Darkness. Now we were past the thing.

"Let's re-rig and try once more," said Cap, deflated.

And so they did.Still nothing. It was a noble try. Tired, disappointed, we started to disperse, then, suddenly:

The bridge phone rang. "Hey!" said Robert who'd been listening all the while on his acoustic receiver,

"I'm getting a surface signal! It's up!"

"There!" Greta shouted, "A strobe light! Right astern!"

Then, the celebration, all smiles, handshakes and hugs all around as they brought the marine-growth encrusted object onto the after deck, and we stood in a circle admiring it.

We had been privileged over the last eight hours to witness a sterling feat of seamanship by the bridge and the deck. Those of us who've sailed more than once aboard Knorr were not surprised, but that doesn't diminish our admiration and respect. But here also was an exquisite example of the essence of at-sea oceanography that uniquely braided combination of science, heavy industry, high-tech electronics, and demanding ship handling. That, for me, makes this little microcosm endlessly fascinating.