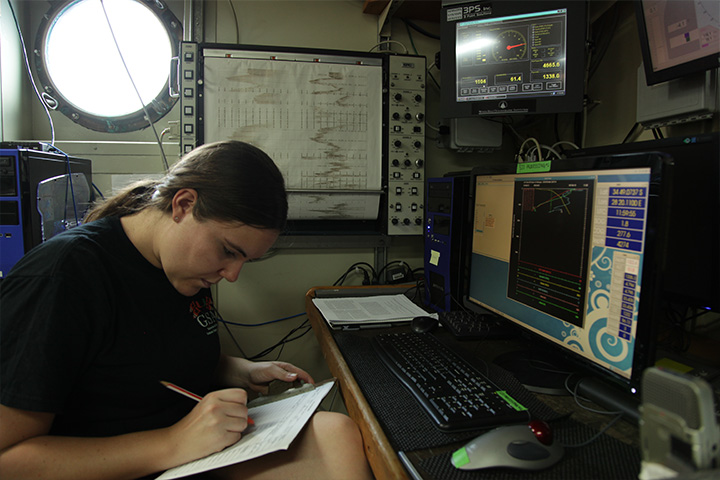

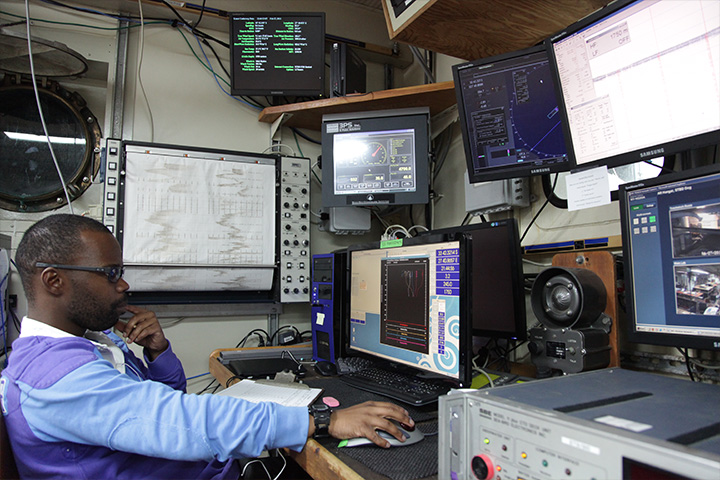

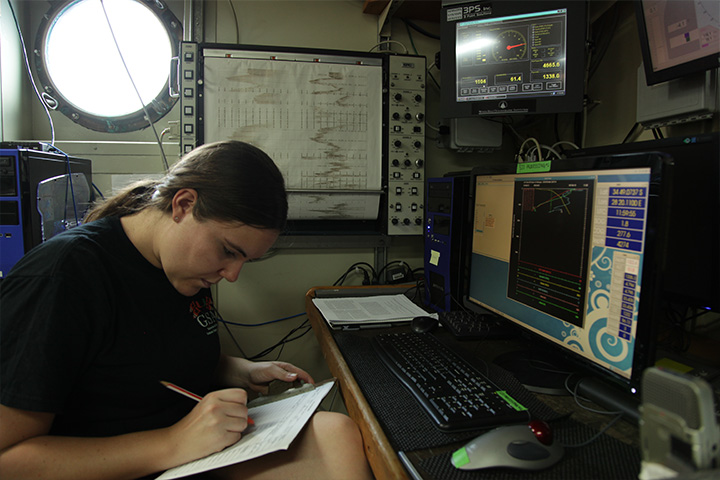

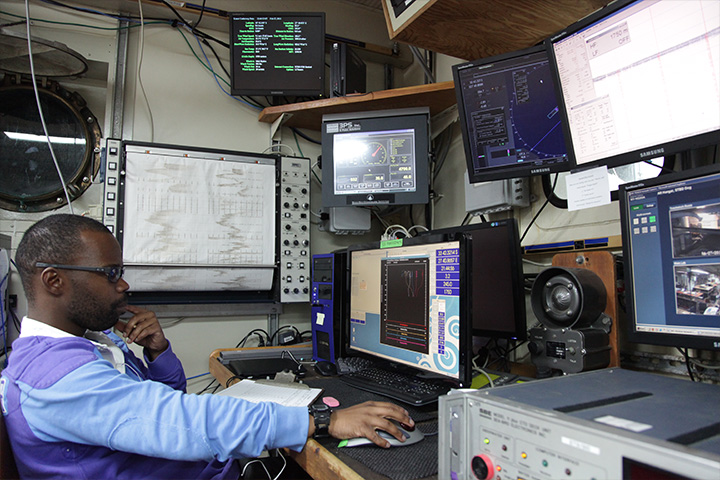

"Winch, lab. Target depth is four-five-seven-zero meters. Take the it down at 60 meters per second."

"Roger. Six-zero."

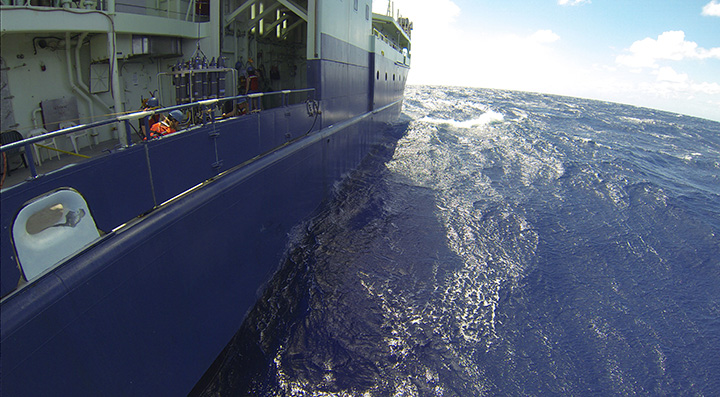

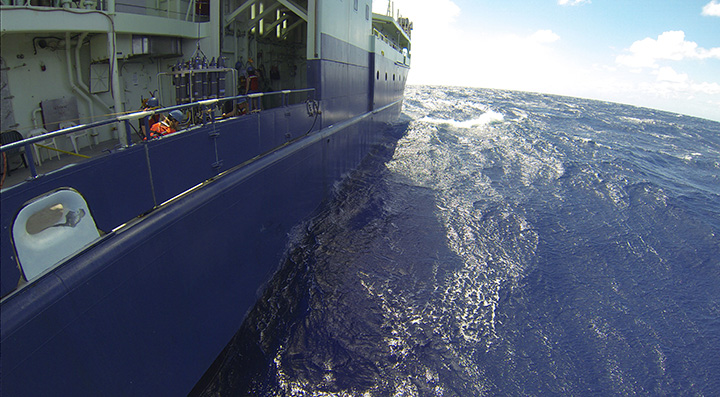

And so begins another of the 67 CTD casts during this cruise, another shot at measuring the ocean. So what do you measure when you seek to understand what Shakespeare called the "vasty deep? It's a secretive thing, the ocean, resistant, and recalcitrant, violent at times, deep and opaque all the time. But in one major aspect it cooperates with the poor oceanographer trying to glean its ways and means: A parcel of water has an individual identity, a fingerprint, in the form of temperature and degree of salinity.

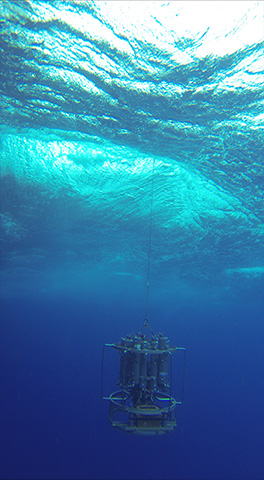

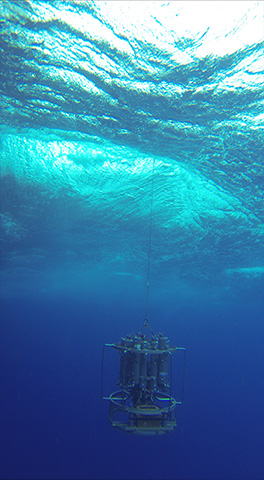

Further, it retains that identity as it courses through the depths. This enables the oceanographer to identify and distinguish it from neighboring water masses and to follow it wherever it goes, assuming she can measure to a high degree of accuracy its T/S fingerprint. That's what the CTD does.

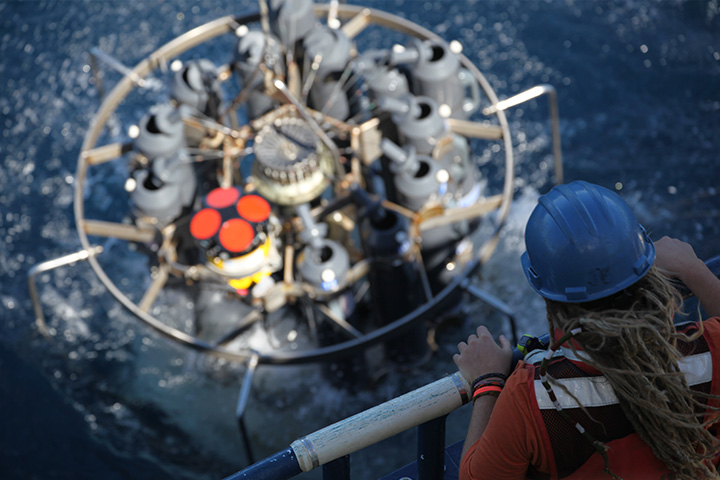

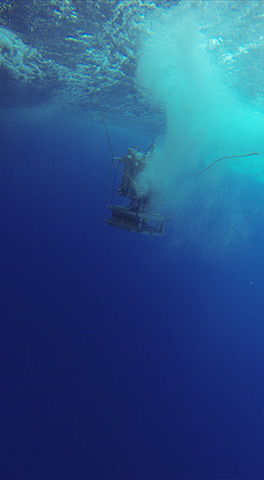

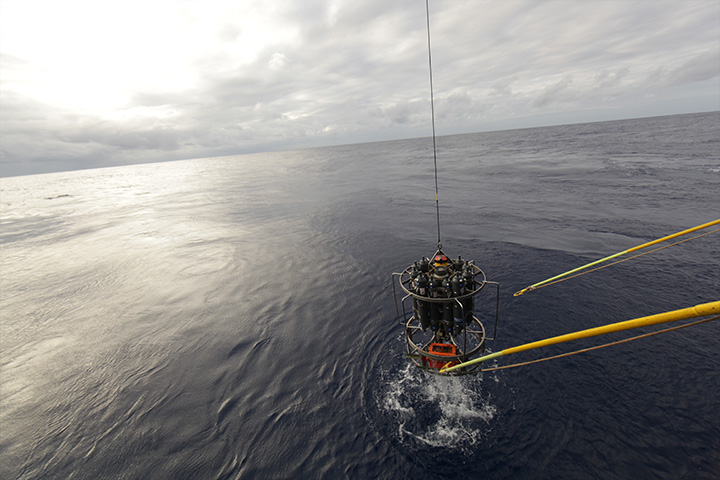

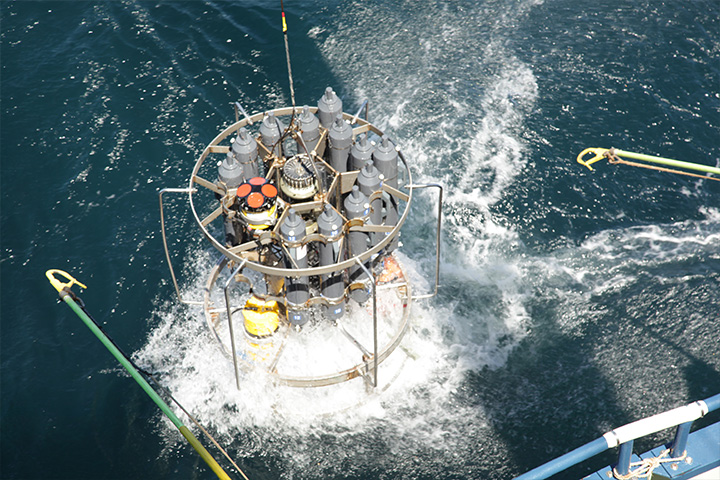

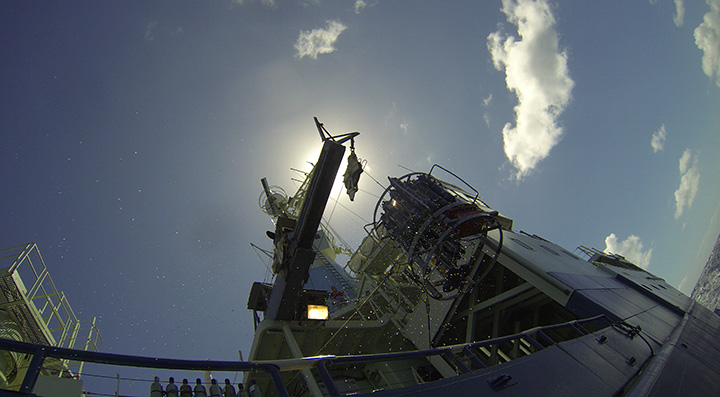

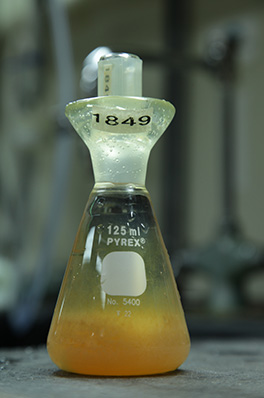

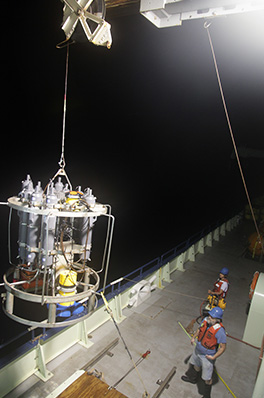

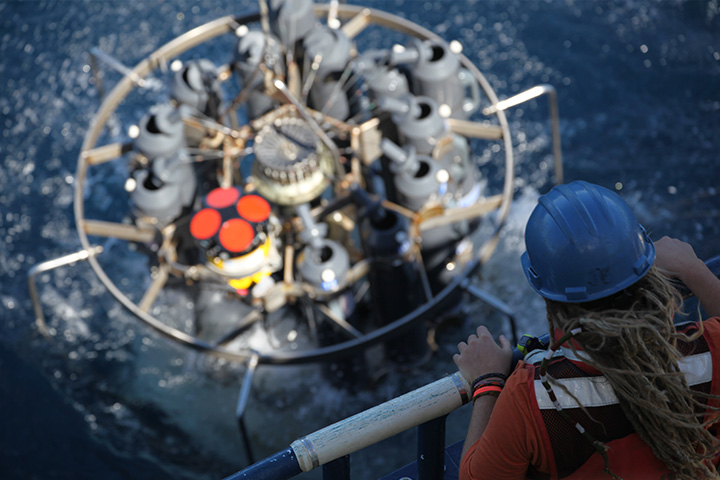

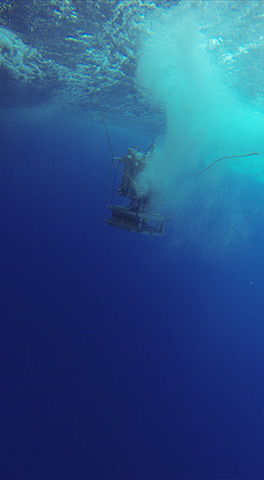

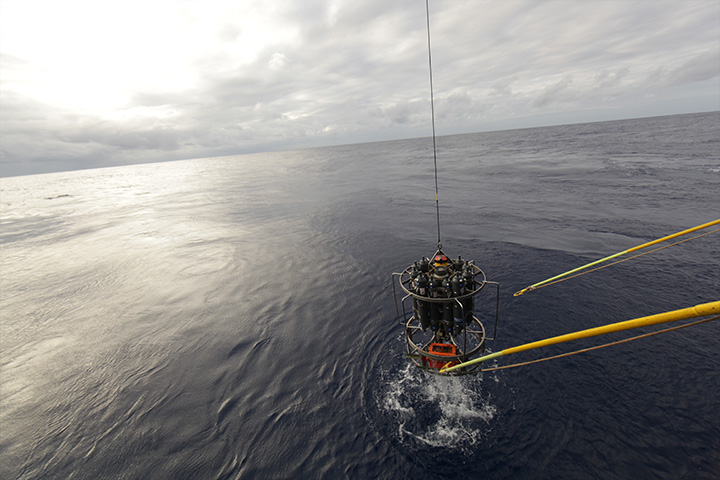

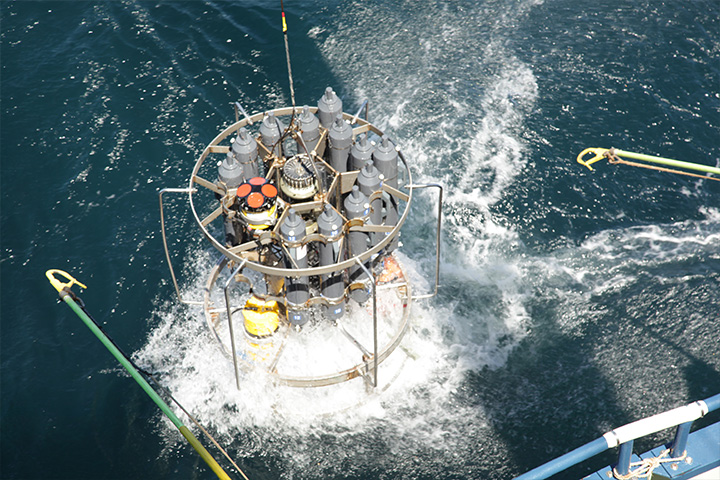

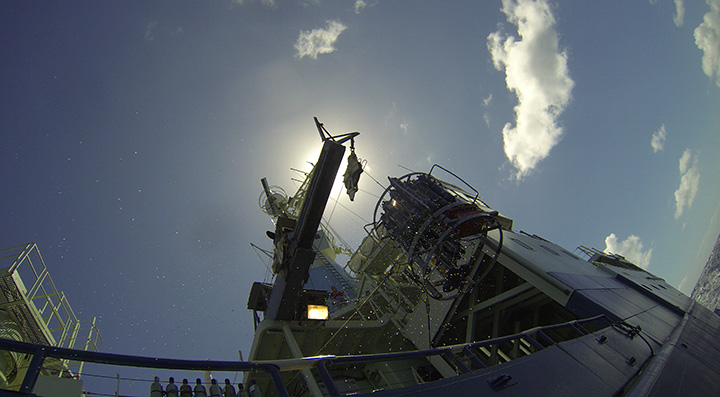

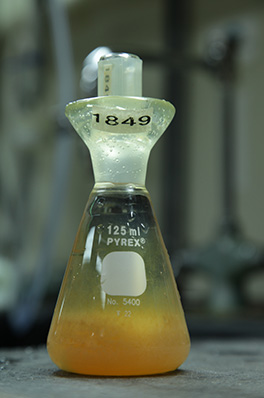

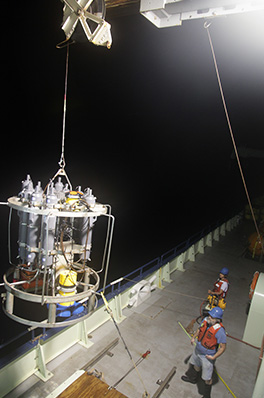

The winch driver and the "operator" at the main-lab computer lower the "package" to within ten meters of the bottom, while temperature and salinity sensors deliver data through the wire in real time. They stop at predetermined depths as they draw the CTD back up through the water column to collect water samples in those grey bottles, like skinny scuba tanks, to use to recalibrate the salinity sensors. (We're talking here about the difference of only a few parts per thousand that distinguish Red Sea water from Antarctic Intermediate Water, both of which are mixed into Agulhas Current water.) It's called the package because it affords a handy platform to mount various instruments depending on the cruise objective. In this case, since Lisa is interested in the velocity of the Agulhas, the package carries an ADCP, which measures the current's speed ("drift" in nautical talk) by pinging sound waves off of particles drifting with the current. If oceanography were carpentry, the CTD would be some really basic tool, say, a saw. Every research vessel carries a CTD; every physical oceanographer uses it on most every cruise.

The advantage and the disadvantage of the CTD is that it's portable. Lisa can choose the points at which she wants to stop the ship and measure the profile of the water column. However, that's only a single-point measurement, a snapshot, that by itself is not particularly revelatory. But over the course of the three annual cruises, she has measured the same 67 CTD sites athwart the Agulhas Current, enabling her to understand the natural wobbles in the current's location. When she combines the CTD data with the long-term velocity measurements from the moorings, she can begin to glean where the current flows and how fast and from this data she can begin to understand longer term changes that may signal changes in climate.

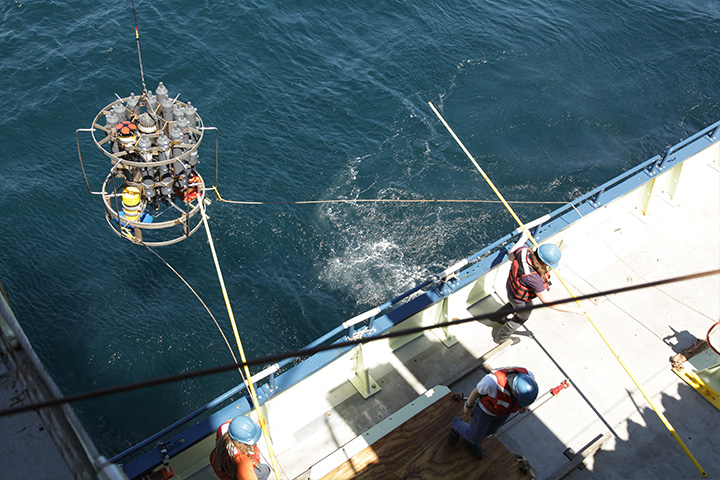

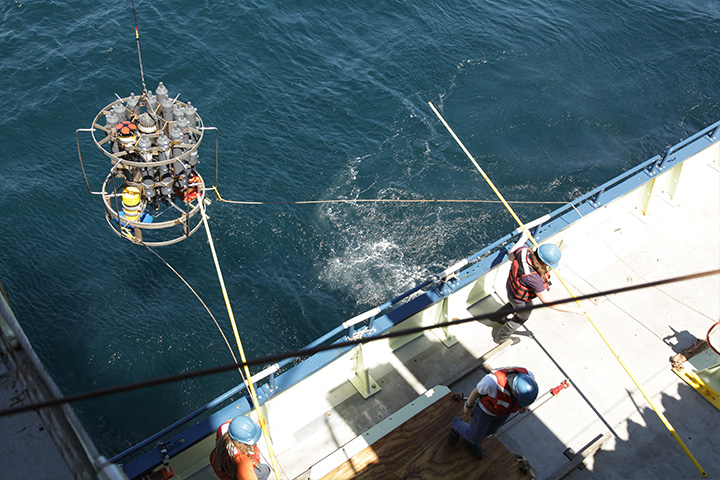

The CTD watches are usually "manned" by Ph.D. and post-doc students, some of whom are on their first sea-going oceanographic expedition, and many of whom are women. They put in long hours day and night, often launching and retrieving the CTD on the pitching deck with boarding seas sloshing around their shins. But by all appearances, they're having fun in each other's company, enjoying as well as learning from the experience.