1. Geostrophic balance:

The geostrophic balance is the primary balance for understanding the ocean circulation. We showed from scaling arguments that at horizontal scales ~100 km geostrophy holds. Geostrophy is the balance between rotation (Coriolis Force) and horizontal pressure gradients.

Fluid wants to flow "downhill" from high to low pressure, but is deflected to the right (left) in the Northern (Southern) Hemisphere by the Coriolis force. When the pressure gradient force and the Coriolis force comes into balance, water moves along isobars with high pressure to the right (left) in the Northern (Southern) Hemisphere.

The challenge with measuring pressure gradients in the ocean is two-fold:

- They must be determined very accurately: a gradient of 1:105 will produce a 1 m/s horizontal flow!

- They must be measured with reference to a geopotential surface (geoid) . This is because deviations from the geoid give rise to fluid flow. The height of the sea surface, or any interfaces, above the geopotential surface is a DYNAMIC HEIGHT. There must be a pressure gradient with respect to a geopotential surface for fluid flow. Using hydrographic measurements collected from a ship at sea (salinity, temperature and pressure) to estimate pressure gradient is a challenge, because there is no way to know the sea surface slope relative to the geoid.

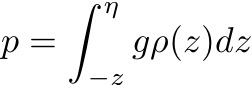

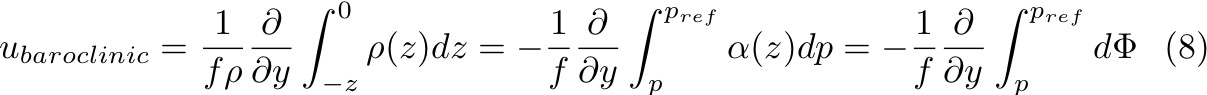

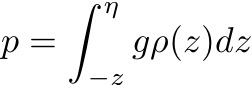

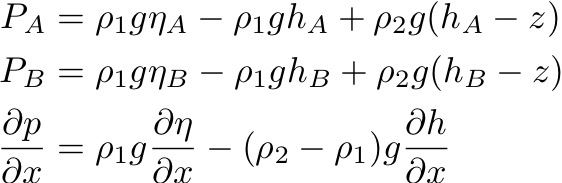

Let's take a look at the equations. The hydrostatic equation in (3) gives:

where η is the sea surface height, g is the acceleration due to gravity, ρ is density, and z is depth. This relation can be split into two components: the pressure due to the height of water above the geoid at z = 0, and the pressure due to the height of water between depth z and the geoid.

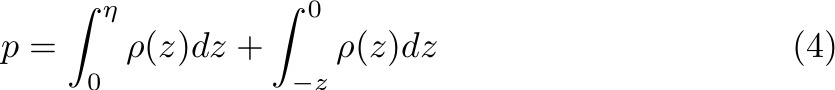

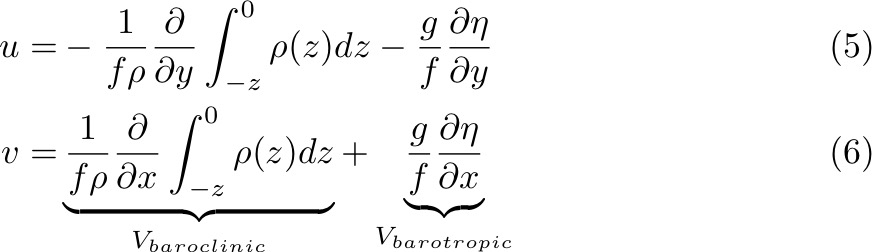

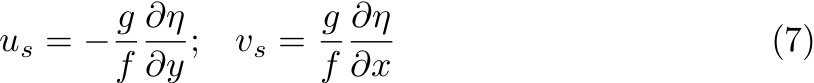

Substituting (4) into (1) and (2) gives:

Here we have also used the Boussinesq Approximation, where the ocean is incompressible (no change in ρ due to increasing pressure), except when calculating the pressure gradient (i.e., except in the hydrostatic equation).

If the ocean is homogeneous and density is constant, then the BAROCLINIC term is zero and the horizontal pressure gradients are the same as at z = 0. This is BAROTROPIC flow. If the ocean is inhomogeneous, with internal changes in ρ, the horizontal pressure gradient has two components: one due to sea surface slope and the other due to horizontal density differences.

What these equations highlight is that, in order to calculate absolute geostrophic velocities from density measurements, one needs to know the slope of the sea surface. Or, one needs to directly measure the surface velocity (or velocity at any depth).

Surface geostrophic velocity can be calculated from sea surface height measurements from satellite altimeters, but not from in situplatforms, such as ships.

2. Dynamic method:

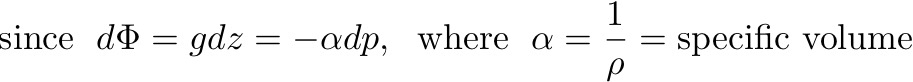

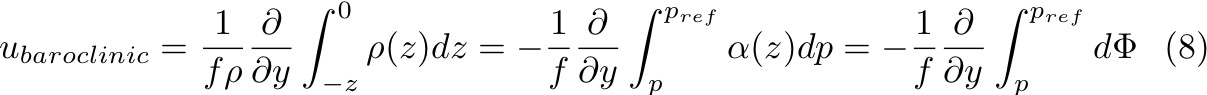

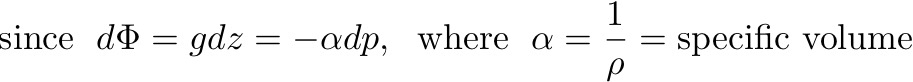

For the baroclinic components of geostrophic velocity, in practice, oceanographers calculate the slope of a constant geopotential surface relative to a constant pressure. This is because the vertical coordinate of hydrographic data is pressure, not depth.

Notice that the geopotential, or dynamic height z = Φ/9.8, is a measure of the work required to lift one unit mass from sea level to a height z, against gravity.

Depth in geopotential meters (dynamic height), depth in meters, and pressure in decibars are almost the same numerically. This is because the contribution of changes in ρ are small compared to the absolute values. For this reason, oceanographers calculate geopotential anomaly, and use this quantity to find the gradient of the geopotential surface. This is much more accurate than subtracting two large numbers, and helps us obtain the 1:107 accuracy that is necessary.

Thus, assuming:

Then the equations become:

This is the dynamic method. Its use is somewhat historical, dating from before the widespread use of calculators and computers, but it remains the most accurate way to calculate geostrophic velocity.

3. Thermal Wind:

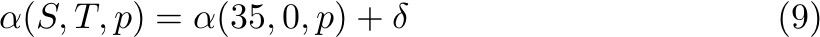

Since we cannot measure the absolute pressure gradient in the ocean from in situ hydrographic measurements, another way to view this problem is to eliminate the pressure gradient terms from the geostrophic relations. We eliminate these terms by differentiating Equations (1) and (2) w.r.t to z, and Equation (3) w.r.t x and y, respectively, and substituting. This allows us to obtain:

From these equations, it is perhaps easier to see the reference level problem. The thermal wind equations give us the vertical shear of the horizontal geostrophic flows and not the absolute velocity. When the equations are integrated w.r.t z there is an unknown constant, or reference velocity, uref, vref, equivalent to the barotropic velocity above.

The assumptions for geostrophic balance:

- Slowly changing, mesoscale to large scale flows: Rossby number U/fL << 1;

- Dissipation is negligible;

- Very small vertical velocities w << u,v;

- Synoptic data: i.e., station data is collected faster than the evolution of the flow;

- Homogeneous data: i.e., T, S, p is measured consistently;

- Station spacing larger than about 10 km;

- Vertical displacement of isopycnals by internal waves is negligible;

- At surface, Ekman flow is negligible.

Important note: Geostrophic velocity is calculated as an integral of a gradient, and so it is an integrated measure and not a pointwise measure. This is very powerful for large scale flows and net-transports. With two density profiles ρ(T,S,p) at either end of a section we can calculate the net geostrophic transport across the section, even though the details of the flow remain unknown. Measuring velocities directly using current meters, however, are point-wise measurements and so to obtain the net section-wide flow you would need to resolve all scales of the velocity field.

4. Margules' Equation:

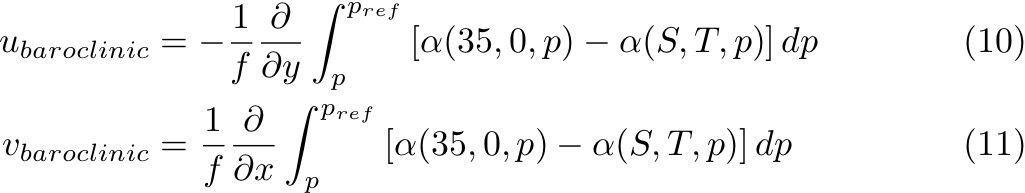

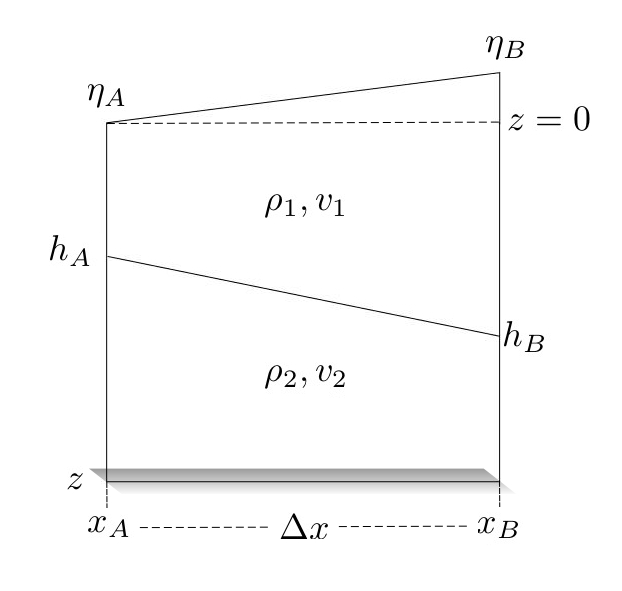

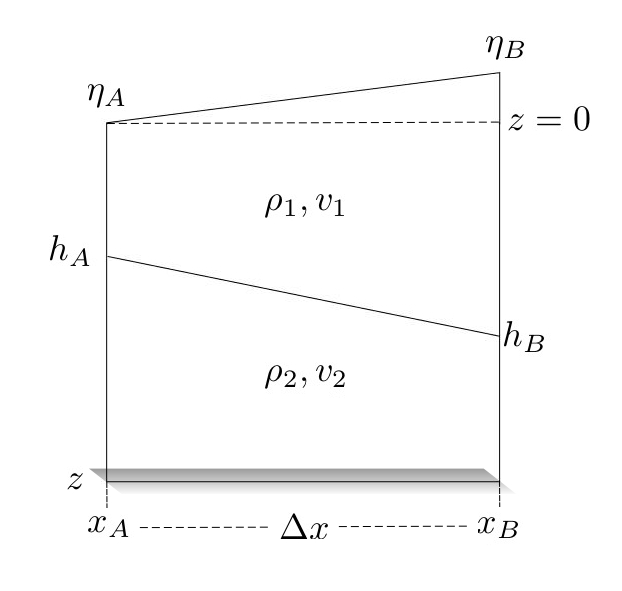

Margules considered a discretely layered ocean with interfaces sloping w.r.t geopotential surfaces. These sloping interfaces give rise to pressure gradients and hence to geostrophic flow. The pressure gradient is given by: PB - PA / (xB - xA):

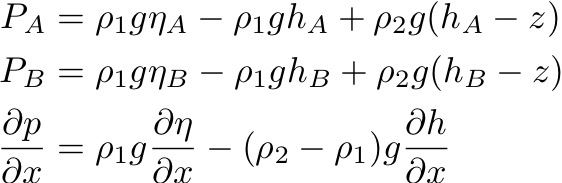

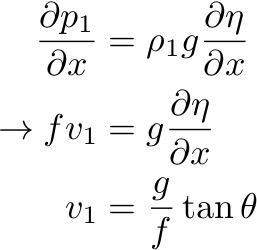

For some depth in the upper layer:

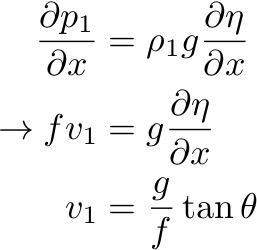

If there is no variation of density in the upper layer, then the velocity is v1 everywhere within that layer. What is v2?

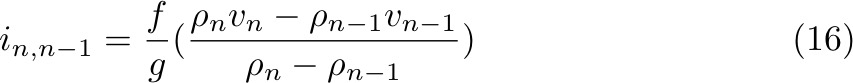

Re-arranging for dh/dx and generalizing to N layers denoted by i (slope between n and n-1th layers), Margules found:

Notice for the case where v2 = 0 (i.e. velocity in lower layer is zero), then dp2/dx = 0 and the two right-hand terms of Equation (14) are equal, such that:

Now, if we notice that ρ2 > ρ1 for a stable ocean then the sea surface slope is OPPOSITE to the interface slope, and it's less by a factor of Δρ/ρ ~ 10-3. This situation is common for the ocean, where upper layer velocities are larger than those in the lower layers, and reduce almost to zero at the bottom (in the deep ocean). This means that the baroclinic pressure gradient is opposing the barotropic pressure gradient.